Who exactly was “Nature’s God” to the American Founders?

6 OctFrom Professor Justin Dyer:

Full Article from Anchoring Truths

“Some of the Founders were Christians, some not so much, but nearly uniformly they believed God created the world and created nature, including human nature. They believed God exercised providence in human affairs, and one aspect of his providential care was in giving humanity natural knowledge of right and wrong. In short, they believed in a Natural Law and a natural lawgiver, something that Christians have long taught is presupposed by but not dependent on Christian revelation.”

The Peculiar Case of Liberalism in American Political History

17 JunHow liberal were the founders? Does the word “Lockean” capture it well? What was the nature of any liberalism they embraced (or rejected)? What had religion to do with any of it? Insightful essay in Law and Liberty by James Patterson. Excerpt:

Recently, political philosophers D. C. Schindler, Mark T. Mitchell, and Patrick Deneen have decided to assess the state of American liberalism and decide whether it is worth defending. In their view, it is not. In Freedom from Reality, Schindler argues that that liberalism has its foundation in the political philosophy of John Locke, and Locke’s philosophy is “diabolical” in its original Greek meaning of “divisive”—that Lockean liberty divides the individual from firm notions of the good, from other individuals, and from attachment to the created world. In The Limits of Liberalism, Mitchell laments how liberalism facilitates the abandonment of place and tradition, in which the autonomous individual senses no obligation to her homeland or even her family, but rather is a citizen of the world committed to personal consumption and identity politics. Finally, Deneen, in his sweeping Why Liberalism Failed, outlines how liberalism relies on pre-liberal institutions to further its ideological goals of technological, economic, and political liberation. Technological liberation frees the individual from physical limits of the body. Economic liberation frees the individual from constraints on satisfying any number of personal preferences or desires. Political liberation frees the individual from external authorities that condemn the improper use of technology or money.

Read together, the summary position would be this: the divisions inherent in Lockean liberty divided individuals from their world, giving them a false sense of freedom from their neighbors and compatriots, and directed them to dissolve communities for the sake of cosmopolitan ends of global capital and imperial redistribution.While Schindler, Mitchell, and Deneen have offered forceful critiques of liberalism, their arguments have shortcomings, and one of them will be the subject of this essay. The shortcoming is methodological. One problem with political philosophy is the tendency to overstate the importance of ideas and understate the importance of other factors, especially contingency and the role of political actors. As a result, liberalism becomes, as Samuel Goldman has argued, a Geist and critiques of liberalism become Geistgeschicten. In other words, liberalism becomes a kind of trans-historical political actor driving the behaviors and events in the world, which then requires describing all those behaviors and events in terms of the advancement of liberalism. While liberal ideas have had a powerful influence on contemporary politics, they are simply insufficient and too diverse to explain either individuals or their responses to contingencies. To provide some needful correction, therefore, I will put the three authors in conversation with the work of Philip Hamburger, who has chronicled the relationship between liberalism as its developed among leading individuals and institutions in the American context.

However, Deenan and other Catholic scholars make a mistake when they attribute either absolutism and liberalism to Protestant Reformers. See Mark David Hall’s article here.

Read the rest here

James Anderson on the Court’s [sleight of hand] Reasoning in Bostock

16 JunFrom James Anderson’s blog:

How then does the Court argue the point? First, it articulates a sufficient condition for violations of Title VII:

If the employer intentionally relies in part on an individual employee’s sex when deciding to discharge the employee—put differently, if changing the employee’s sex would have yielded a different choice by the employer—a statutory violation has occurred. (p. 9)

Having established this condition, it proceeds by way of illustrative examples to show that any SOGI discrimination will inevitably meet this condition and thereby violate Title VII. Here are the two paradigmatic cases offered by the Court:

Consider, for example, an employer with two employees, both of whom are attracted to men. The two individuals are, to the employer’s mind, materially identical in all respects, except that one is a man and the other a woman. If the employer fires the male employee for no reason other than the fact he is attracted to men, the employer discriminates against him for traits or actions it tolerates in his female colleague. Put differently, the employer intentionally singles out an employee to fire based in part on the employee’s sex, and the affected employee’s sex is a but-for cause of his discharge. Or take an employer who fires a transgender person who was identified as a male at birth but who now identifies as a female. If the employer retains an otherwise identical employee who was identified as female at birth, the employer intentionally penalizes a person identified as male at birth for traits or actions that it tolerates in an employee identified as female at birth. Again, the individual employee’s sex plays an unmistakable and impermissible role in the discharge decision. (pp. 9-10)

So here’s the reasoning in the first case. Both employees have the trait attracted-to-men. Only one is fired, and the reason he’s fired is because he’s a man. The other employee has exactly the same trait, but she keeps her job because she’s a woman. Ergo, the first employee was discriminated against based on his sex, which Title VII prohibits.

The problem with the example, though, is that it prejudicially describes the situation so as to deliver the conclusion that there was sex-based discrimination. Suppose we say that the relevant trait is not attracted-to-men but rather same-sex-attracted. Under that description, the biological sex of the employee turns out to be irrelevant: “changing the employee’s sex” would not have “yielded a different choice by the employer.” Presumably what the employer objects to is homosexuality as such, regardless of whether it’s male or female homosexuality. (I suppose there could be cases where an employer discriminates against male homosexuals but not female homosexuals, or vice versa, but obviously such cases aren’t in view here.)

Note in particular the reference to “the employer’s mind” in the excerpt above. What is the objectionable trait in the employer’s mind? Is it attraction to men? Or is it same-sex attraction? Clearly the two are not logically or conceptually equivalent. But the entire argument hangs on the first being the relevant trait rather than the second. Yet it’s most plausibly the second that serves as the basis for the discrimination. If that’s the case, the Court’s argument collapses.

The same analysis can be applied to the second example. In the decision of the employer, is the relevant trait identifies-as-male? Or is it identifies-as-other-than-birth-sex? If it’s the second, then there’s no discrimination based on sex, because “changing the employee’s sex” would not yield “a different choice by the employer.” Again we see that the example has been prejudicially constructed so as to ‘trigger’ the Court’s test for sex-based discrimination.

That’s not quite the end of the issue, however. Notice that the Court’s test asks whether “the employer intentionally relies in part on an individual employee’s sex when deciding to discharge the employee” (emphasis added). Gorsuch anticipates the kind of rebuttal I gave above and offers a response to it, namely, that an employer cannot determine whether an employee is homosexual or transgender without reference to the employee’s sex. Thus, for example, Frank can’t tell whether Andy is gay without knowing that Andy is male, and so Frank would have to “rely in part” on Andy’s sex in any decision to hire or fire him on the basis of Andy’s sexual orientation.

Here’s how Gorsuch tries to make the argument, again by way of example:

There is simply no escaping the role intent plays here: Just as sex is necessarily a but-for cause when an employer discriminates against homosexual or transgender employees, an employer who discriminates on these grounds inescapably intends to rely on sex in its decisionmaking. Imagine an employer who has a policy of firing any employee known to be homosexual. The employer hosts an office holiday party and invites employees to bring their spouses. A model employee arrives and introduces a manager to Susan, the employee’s wife. Will that employee be fired? If the policy works as the employer intends, the answer depends entirely on whether the model employee is a man or a woman. To be sure, that employer’s ultimate goal might be to discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. But to achieve that purpose the employer must, along the way, intentionally treat an employee worse based in part on that individual’s sex. (p. 11; italics original, bold added)

The point is clear: the employer’s decision to fire the “model employee” depends in part on his recognition that the employee is female. Thus, reasons the Court, the discrimination “relies in part” or “is based in part” on the employee’s sex. The employer is quite self-conscious about this. The employer knowingly (and thus intentionally) reaches his decision partly on the basis of the employee’s sex.

The flaw in this argument is that it conflates two distinct things:

- discrimination on the basis of X

- discrimination on the basis of Y, with reliance on X in the process

That one has to take X into account in order to discriminate on the basis of Y simply does not entail that one is thereby discriminating on the basis of X. It’s entirely possible to adopt a normative stance with respect to Y (favoring some Ys over other Ys) without adopting any normative stance with respect to X, even if one has to take X into account when determining Y.

To make things more concrete, consider this scenario. George owns a store that sells shoes for both men and women. He hires two people as store clerks, Andy and Barbara. Over time, George notices that some of his stock is going missing. Based on good evidence, he concludes that one of his two employees has been stealing items. As he further investigates, he discovers that all the stolen items are men’s shoes. Reasoning that a man would be far more likely to take men’s shoes than a woman, he concludes that Andy is the culprit and fires him.

Now clearly George’s decision “relied in part” on Andy’s sex. It was “based in part” on the fact that Andy is a man rather than a woman. Moreover, George’s reliance on that fact was quite intentional. But should we conclude that George is guilty of discrimination based on sex? Did George violate Title VII?

If you think so, I doubt anything else I could say would persuade you otherwise. The “reliance on sex” in George’s decision-making is clearly benign, yet it parallels the “reliance on sex” in Gorsuch’s hypothetical scenario above. What was the relevant trait or action in George’s decision to fire Andy? Was it male-shoe-stealing or was it simply shoe-stealing? What was George’s motivation for firing Andy? Did it involve any prejudice regarding Andy’s sex? The answers to these questions should be obvious.

Enough has been said, I trust, to demonstrate the fallacious nature of the argument at the heart of the Court’s opinion. Even granting what the Court claims about “the ordinary public meaning” of the Title VII statute, the notion that “discrimination based on homosexuality or transgender status necessarily entails discrimination based on sex” is just flat-out confused. It’s a bad ruling that will have very harmful consequences (and not just for religious employers).

If you have the time and patience, I would encourage you to read all three opinions (the majority and the two dissents). Alito’s dissent is devastating; he completely dismantles Gorsuch’s arguments and lays bare the many problematic implications of the Court’s decision.

June 15, 2020, was not a good day for the Supreme Court of the United States.

Ryan Anderson on Gorsuch’s Reasoning

16 JunSum: “Justice Gorsuch’s position would either require the elimination of all sex-specific programs and facilities or allow access based on an individual’s subjective identity rather than his or her objective biology. When Gorsuch claims that “transgender status [is] inex¬tricably bound up with sex” because “transgender status” is defined precisely in opposition to sex, he presumes the very sex binary his opinion will help to further erode.”

Can political liberalism and religious liberty (accommodation) coexist?

29 AprCan political liberalism and religious liberty (accommodation) coexist?

Similar argument made in Smith’s game-changing book Pagan and Christian in the City: “The Supreme Court might soon address this issue. Four Supreme Court justices (led by Justice Samuel Alito) began 2019 by suggesting their willingness to revisit a landmark decision with stark views on this question. In the 1990 case Employment Division v. Smith, a five-justice majority (led by Justice Antonin Scalia) made it virtually impossible to secure, under the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause, religious-based exemptions to laws that apply to everyone and do not overtly or covertly discriminate against religion (what lawyers call “neutral laws of general applicability”). The Smith decision presumes a deep tension between religious exercise and the common good. In Smith’s view, the democratic process must almost always resolve that tension. Courts, therefore, almost always deny religious accommodation requests. Justice Alito and his colleagues, however, said Smith “drastically cut back on the protection provided by the Free Exercise Clause,” and effectively invited requests to reverse it.

Revisiting Smith possesses significant cultural salience. Many of today’s progressives, conservatives, and libertarians share — knowingly or not — Smith’s critical shortcoming: a failure to explain why religion in particular and religious exercise in particular should shape the common good, even when they go against the grain of secular visions adopted in law. Revisiting Smith provides an opening to address this shortcoming. The Court should take it, as this oversight puts the American tradition of self-government at stake.

Smith and many elements of the modern American left and right possess this shortcoming because they evaluate the social worth of religious pluralism against some set of liberal values that, in their view, should supersede religious duties. For Smith, the superseding value is majoritarianism: Religious pluralism is good when democratic majorities decide it is worth their solicitude. For progressives, religious pluralism is good to the extent it supports what law professor Mark Movsesian calls “equality as sameness.” Any religious practice, institution, or tradition that understands equality differently is publicly unacceptable. For some conservatives and libertarians, religious pluralism is good simply because self-expression is good. On this view, religious liberty deserves protection simply because self-expression deserves protection — nothing particular to religion here does any work. Finally, for other conservatives who dispute that the common good is served by diverse religious expression, religious liberty is part of the common good only to the extent it establishes a particular religion’s orthodoxy.

It is not surprising that what Stanford’s Michael McConnell called “the most thoroughly liberal political community in the history of the world” would strive to define even religion around liberal ideals — but it is problematic. Liberal democracy, as Alexis de Tocqueville observed, is “particularly liable to commit itself blindly and extravagantly to general ideas.” This is partly because liberalism is, as Samuel Huntington put it in Conservatism as an Ideology, an “ideational” ideology. It “approach[es] existing institutions with an ‘ought demand’ that the institutions be reshaped to embody the values of the ideology.” This “ought demand” is present in social-contract theory, and it poses a particular problem for religious liberty. More often than not, religious exercise is manifested in rituals and institutions that are prior to — and claim to outlast — political liberalism. Reshaping religious exercise around liberal values can therefore dilute religion.

The consequences of dilution are not limited to religion. As our founders recognized, diluting religious exercise poses a problem for political liberalism; self-government presupposes certain moral virtues that religion cultivates and liberalism does not. In a culture that does not appreciate a distinct contribution from religious exercise, engagement with religion, both personally and in public life will erode — along with the corresponding cultivation of religious exercise’s personal and public goods.”

Read the rest from National Affairs (and definitely read Smith’s book Pagan and the Christian in the City). Smith argues that there has been and always will be a vying for supremacy between the transcendent religion of Christianity and the immanent religion of modern paganism. Compromises in the name of political liberalism are at best short-lived and at worst preferential towards modern paganism. Any worldview that finds meaning and purpose and epistemological grounding in this world rather than another will always marginalize the transcendent religionists to the outer periphery of society (it’s a logical necessity of sorts).

Christians, thankfully, have been standing against the social acids of sexual sin since ancient Rome.

17 OctFrom Tim Challies:

we are experiencing a sexual revolution that has seen society deliberately throwing off the Christian sexual ethic. Things that were once forbidden are now celebrated. Things that were once considered unthinkable are now deemed natural and good. Christians are increasingly seen as backward, living out an ancient, repressive, irrelevant morality.

But this is hardly the first time Christians have lived out a sexual ethic that clashed with the world around them. In fact, the church was birthed and the New Testament delivered into a world utterly opposed to Christian morality. Almost all of the New Testament texts dealing with sexuality were written to Christians living in predominantly Roman cities. This Christian ethic did not come to a society that needed only a slight realignment or a society eager to hear its message. No, the Christian ethic clashed harshly with Roman sexual morality. Matthew Rueger writes about this in his fascinating work Sexual Morality in a Christless World and, based on his work, I want to point out 3 ugly features of Roman sexuality, how the Bible addressed them, and how this challenges us today.

The Radicals, not the Protestants, have won. From Michael Horton

16 OctMuch of the hoopla surrounding the five hundredth anniversary of the Protestant Reformation has been blather. On October 31, 2016, at a joint service in Lund, Sweden, Pope Francis and the president of the World Lutheran Federation exchanged warm feelings. Rev. Martin Junge, general secretary of the mainline Lutheran body, said in a press release for the joint service, “I’m carried by the profound conviction that by working towards reconciliation between Lutherans and Catholics, we are working towards justice, peace and reconciliation in a world torn apart by conflict and violence.” Acknowledging Luther’s positive contributions, the pope spoke of how important Christian unity is to bring healing and reconciliation to a world divided by violence. “But,” he added, according to one report, “we have no intention of correcting what took place but to tell that history differently.”

Perhaps the most evident example of missing the point is the statement last year in Berlin by Christina Aus der Au, Swiss pastor and president of an ecumenical church convention: “Reformation means courageously seeking what is new and turning away from old, familiar customs.” Right, that’s what the Reformation was all about: average laypeople and archbishops gave their bodies to be burned and the Western church was divided, because people became tired of the same old thing and were looking for nontraditional beliefs and ways of living—just like us!

The Wall Street Journal reports a Pew study in which 53 percent of US Protestants couldn’t identify Martin Luther as the one who started the Reformation. (“Oddly, Jews, atheists, and Mormons were more familiar with Luther.”) In fact, “Fewer than 3 in 10 white evangelicals correctly identified Protestantism as the faith that believes in the doctrine of sola fide, or justification by faith alone.”1

Many today who claim the Reformation as their heritage are more likely heirs of the Radical Anabaptists. In fact, I want to test the waters with an outlandish suggestion: Our modern world can be understood at least in part as the triumph of the Radicals. At first, this seems a nonstarter; after all, the Anabaptists were the most persecuted group of the era—persecuted not only by the pope, but also by Lutheran and Reformed magistrates. Furthermore, today’s Anabaptists are pacifists who generally eschew mingling with outsiders, rather than revolutionary firebrands such as Thomas Müntzer, who led insurrections in the attempt to establish end-time communist utopias (with themselves as messianic rulers).

I’m not talking about Amish communities in rural Pennsylvania. In fact, I don’t have in mind specific offshoots, like Arminian Baptists, as such. I’m thinking more of the Radical Anabaptists, especially the early ones, who were more an eruption of late medieval revolutionary mysticism than an offshoot of the Reformation. I have in mind a utopian, revolutionary, quasi-Gnostic religion of the “inner light” that came eventually to influence all branches of Christendom. It’s the sort of piety that the Reformers referred to as “enthusiasm.” But it has seeped like a fog into all of our traditions.

Bernie Sanders and American Laicite

26 JunLove this post from my fb friend David Koyzis, whose book Political Visions and Illusions (https://www.amazon.com/dp/B001HL0E0M/ref=dp-kindle-redirect…) I continuously recommend to students. It touches directly on the subject matter of my own research with Mike Lavender on a church/state phenomena we think America is currently experiencing; a concept we call “American Laicite” (the tendency in American political and social institutions to depart from either a strict separation model, where religion is excluded from public life or accommodationist model, where religion is indiscriminately included in public life, towards a selective accommodationist model where religion is included, and can avoid chastisement or penalties, so long as it accommodates itself to a higher creed driven by an alternate secular, humanist, or progressive worldview or sorts.

During last year’s presidential election campaign, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, a latecomer to the Democratic Party, positioned himself as a voice for the downtrodden against big moneyed interests, something that many Americans, especially the young, found deeply attractive. In so doing, Sanders drew on a deep tradition of social justice with biblical roots, as evidenced in his powerful address to Liberty University two years ago. Recognizing that “there is no justice when so few have so much and so many have so little,” he laudably demonstrated his concern for the economically disadvantaged in our society. However, judging from his questioning last week of Russell Vought, the President’s nominee for deputy director of the Office of Management and Budget, Sanders appears not to understand that there is no justice where religious liberty lacks protection.

At issue was a blog post Vought had written as an alumnus of Wheaton College, a Christian university near Chicago, in response to a controversy involving one of its faculty members. The offending passage was this: “Muslims do not simply have a deficient theology. They do not know God because they have rejected Jesus Christ his Son, and they stand condemned.” While it may sound harsh to a nonchristian, Vought was in no way suggesting that Muslims cannot be good citizens or should be treated severely by the governing authorities. He was simply reiterating what the vast majority of Christians have believed for two millennia: that Jesus is the way, the truth and the life, and that no one comes to the Father except through him (John 14:7).

But this appears not to satisfy Sanders, who has shown himself in this respect to be a good student of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), the Genevan political philosopher who famously proposes an ostensibly tolerant civil religion at the end of Book IV of his Social Contract.

There is therefore a purely civil profession of faith of which the Sovereign should fix the articles, not exactly as religious dogmas, but as social sentiments without which a man cannot be a good citizen or a faithful subject. While it can compel no one to believe them, it can banish from the State whoever does not believe them — it can banish him, not for impiety, but as an anti-social being, incapable of truly loving the laws and justice, and of sacrificing, at need, his life to his duty. If any one, after publicly recognising these dogmas, behaves as if he does not believe them, let him be punished by death: he has committed the worst of all crimes, that of lying before the law.

The dogmas of civil religion ought to be few, simple, and exactly worded, without explanation or commentary. The existence of a mighty, intelligent and beneficent Divinity, possessed of foresight and providence, the life to come, the happiness of the just, the punishment of the wicked, the sanctity of the social contract and the laws: these are its positive dogmas. Its negative dogmas I confine to one, intolerance, which is a part of the cults we have rejected.

Those who distinguish civil from theological intolerance are, to my mind, mistaken. The two forms are inseparable. It is impossible to live at peace with those we regard as damned; to love them would be to hate God who punishes them: we positively must either reclaim or torment them. Wherever theological intolerance is admitted, it must inevitably have some civil effect; and as soon as it has such an effect, the Sovereign is no longer Sovereign even in the temporal sphere: thenceforce priests are the real masters, and kings only their ministers.

One needn’t dig too far beneath the surface to discern rather quickly that Rousseau’s offer of tolerance could scarcely be more intolerant. Anyone who believes that God has revealed himself in specific ways to specific people and that even the state derives its authority from God cannot be a good citizen of the republic.

On being a Southener

18 AprBy Barton Swaim at New Criterion:

Two-thousand-eleven marked the 150th anniversary of the firing on Fort Sumter, the Battle of Bull Run, and the beginning of America’s bloodiest war. In Charleston and in fields outside Manassas, Virginia, war re-enactors put on lavish displays of martial conflicts. Essays and articles on the War appeared in all the major newspapers, books on the conflict were widely reviewed, and PBS again ran Ken Burns’s documentary series The Civil War, provoking at least one observer to express irritation that the Confederacy lends itself so easily to romantic portrayal. Once again (or so I imagine) people found themselves asking, perhaps with the red and blue map of Electoral College results in the back of their minds: Who are these Southerners? Are they the racists and political reactionaries we’ve always suspected them to be? Are they Americans in the deepest, most genuine sense, or is the South some aberration about which we ought to be embarrassed?

Jacques Barzun once remarked that Darwin’s Origin of the Species is one of those books on which people have always felt free to discourse without having read it. That’s true of the American South, too, and has been for a long time. “In the Southern states, gaming, fox hunting and horse-racing are the height of ambition; industry is reserved for slaves”: so wrote a twenty-six-year-old Noah Webster who had never been further south than New York. Exactly that sort of confident ignorance has long animated the American entertainment industry. Every Southerner has a favorite complaint: the apparent inability of film and television producers to find actual Southerners to play the part of Southerners; the routine association of the South with incest and abject stupidity; the location of all forms of bigotry in the South, even those for which Southerners aren’t known; and of course the amazingly resilient idea that the Civil War was merely and exclusively about racism—a belief lampooned by Michael Scott (played by Steve Carell) in the television comedy “The Office.” Defending himself against imputations of racism, Michael remarks, “As Abraham Lincoln once said, ‘If you are a racist, I will invade you with the North.’”

Southerners themselves, or at least the writers and intellectuals among them, have long been preoccupied with defining Southern identity—often with results that confuse rather than clarify. Before the War, a number of influential Southern writers circulated the bogus notion that Southerners were descended from Cavaliers (mannerly, aristocratic, unmindful of money) and Northerners from Puritans (earnest, plain in habits, inclined to moneymaking pursuits). After the War, a disparate variety of journalists, industrialists, and politicians promoted something they called the “New South,” a region that would foster economic and cultural vibrancy without giving in to the worship of Mammon (or, for some, to racial equality). It was against this latter collection of hopes and ideas that the Agrarian intellectuals reacted in I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition. The twelve authors of that book—among them Robert Penn Warren, John Crowe Ransom, Allen Tate, and Frank Owsley—inveighed against the project, as they felt it to be, to make the South more like the North: more vulnerable to the cultural volatility and spiritual shallowness of an unregulated economy, more hospitable to radical individualism.

Perhaps not all that was lost in the Lost Cause was a good riddance

17 AprForm Dr. Boyd Cathey:

it was a war between two ideas of government, and, in reality, two ideas of history and progress. For the North, which now controlled the Federal government, it was a war to suppress what was seen as a rebellion against constituted national authority. For the states of the Southern Confederacy, it was a defense of their inherited and inherent rights under the old Constitution of 1787, rights that had never been ceded to the Federal government. And, more, it became for them a Second War for Independence against an arbitrary and overreaching government that had gravely violated that Constitution.

Thus, at Appomattox were set into motion momentous events in the future of the reconstituted American nation. With the defeat of the South, the restraints on industrial, and, eventually, international capitalism were removed. The road to centralized government power was cleared. But even more significantly, there was a sea change in what we might call “the dominant American philosophy.”

In the old ante-bellum Union the South had acted as a kind of counter-weight to the North and a quickly developing progressivist vision of history. Certainly, there were notable Southerners who shared the growing economic and political liberalism of their fellow citizens north of the Mason-Dixon Line (e.g, DeBow’s Review). Yet, increasingly in the late ante-bellum period, the most significant voices in the Southland echoed a kind of traditionalism somewhat reminiscent of the serious critiques being made in Europe of “the Idea of Progress” and of the deleterious effects of 19th century liberalism.

Consequences of secularization: replacing religion with secular and pagan ideologies, which is worse for us all

23 MarFrom Peter Beinart in the Atlantic

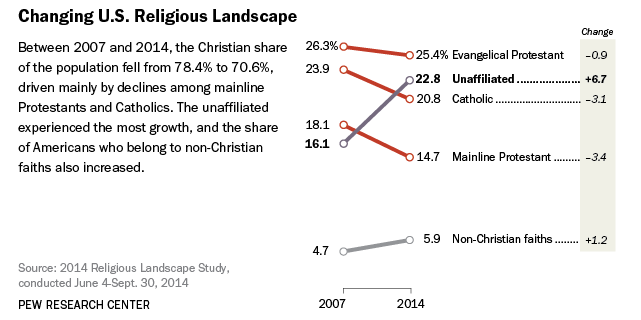

“Over the past decade, pollsters charted something remarkable: Americans—long known for their piety—were fleeing organized religion in increasing numbers. The vast majority still believed in God. But the share that rejected any religious affiliation was growing fast, rising from 6 percent in 1992 to 22 percent in 2014. Among Millennials, the figure was 35 percent.

Some observers predicted that this new secularism would ease cultural conflict, as the country settled into a near-consensus on issues such as gay marriage. After Barack Obama took office, a Center for American Progress report declared that “demographic change,” led by secular, tolerant young people, was “undermining the culture wars.” In 2015, the conservative writer David Brooks, noting Americans’ growing detachment from religious institutions, urged social conservatives to “put aside a culture war that has alienated large parts of three generations.”

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/04/breaking-faith/517785/

Lest we forget about the last 8 years regarding religious liberty. A summary

19 JanFrom Andrew Walker and Josh Wester in the National Review:

For eight years, the Obama administration brought fundamental change to American life. As the administration comes to an end, it is appropriate to evaluate its legacy. And though many such assessments will be written, among the most important issues to consider is the Obama administration’s record on religious liberty. As we’ll argue based on episodes throughout President Obama’s time in office, this administration oversaw an unprecedented effort to intentionally malign and dethrone religious liberty as a central pillar in American political and civil life. Notwithstanding this overall record, and though neither of us is a political supporter of Obama, we applaud the efforts made by the administration in a few areas to champion religious liberty. In 2008, Obama was a U.S. senator and presidential candidate publicly opposed to same-sex marriage. Much has changed in eight years. For the foreseeable future, the legacy of the Obama administration will rest on two alliterative, colossal initiatives that have left an indelible crater on the landscape of religious liberty: Obamacare and Obergefell v. Hodges.

Read more at: http://www.nationalreview.com/article/443933/obama-administration-has-troubled-religious-liberty-legacy

Two Americas

20 OctGertrude Himmelfarb in her book One Nation, Two Cultures (2010) argued that America is comprised of two distinct cultures. A traditionalist one (conservative, Puritan heritage) and a dissident one (counterculture of the 1960s). She wrote:

As a minority, the traditionalist culture labors under the disadvantage of being perennially on the defensive. Its elite — gospel preachers, radio talk show hosts, some prominent columnists, and organizational leaders–cannot begin to match, in numbers or influence, those who occupy the commanding heights of the dominant culture; professors presiding over the multitude of young people who attend their lectures, read their books, and have to pass their exams; journalists who determine what information, and what ‘spins’ on that information, come to the public; television and movie producers who provide the images and values that shape the popular culture; cultural entrepreneurs who are ingenious in creating and marketing ever more sensational and provocative products. An occasional boycott by religious conservatives can hardly counteract the cumulative, pervasive effect of the dominant culture.

A Taxonomy of Conservatism

2 SepFrom Peter Lawler:

Americans today are understandably confused about what it means to be a conservative. The Republican nominee, for example, doesn’t seem to be one. And the conservative movement seems to be as fractured as our republic. After this election cycle, conservatives are going to have rethink who they are and what they’re supposed to do.

Who will be there to lead the rethinking and realigning? Here’s a list of nine conservative factions or modes of thought around today. Consider this your beginner’s guide to understanding the rivals on the right and the issues that animate them. It goes without saying that this list isn’t complete, and you might identify with more than one group. That issue of identity has become bigger than ever over the past year. The advantage of living through startling and unprecedented events is that we conservatives have no choice but to reflect deeply once again about who we are.

1. Growth Conservatives

They are associated with the Wall Street Journal and the so-called big donors. They think the main reform America needs today is to cut taxes and trim regulations that constrain “job creators.” On one hand, they think that America is on “the road to serfdom.” On the other hand, they often think this is a privileged moment in which conservative reform—such as the passing of right-to-work laws—is most likely to succeed.

2. Reform Conservatives

These conservatives think that growth is indispensable and that it’s unreasonable to believe America could return to a time when global economic dominance and lack of birth dearth made possible unions, a mixture of high taxes and unrivaled productivity, and a secure system of entitlements. So they’re for prudent entitlement reform. They’re also for a tax policy that treats Americans not only as free individuals but also as, for example, struggling parents who deserve tax credits. In our pessimistic time, reform conservatives are also characterized by a confidence that nobody should ever bet against America, that we’re up to the challenges we face. Their intellectual leader is the think-tanker Yuval Levin, and they have the ears of Speaker of the House Paul Ryan and Senator Marco Rubio.

– See more at: https://home.isi.org/confused-students-guide-conservatism#.V7heLTic2Fx.twitter

Is America drifting away from its Virginian – New England founding?

29 AugFrom Peter Lawler:

There were the original settlements — one in Virginia and one in New England. And ever since that time, you’ve had two conflicting impulses in American political life. The Virginians are all about liberty, as in Mr. Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence. And the New Englanders — the Puritans or the Pilgrims — are all about participatory civic equality through the interdependence of the spirit of religion and the spirit of liberty. America works best when the Americans harmonize by curbing the excesses of both Virginia and New England. That’s what the compromise that was the completed Declaration of Independence, as opposed to Jefferson’s rough draft Yo, did. You see that in Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, which dedicated our country to the proposition that all men are created equal. And you see that in the rhetoric of Martin Luther King Jr. at his best. The Puritans, in general, tend to be too moralistically intrusive, to turn every sin into a crime. They’re an important source of our history of taking sexual morality very seriously, and for believing that American liberty depends on Americans sharing a common religious morality. They’re also the source of some of our most ridiculous and meddlesome legislation, such as prohibition (and, in some indirect way, Mayor Bloomberg’s legal assault on our liberty to drink giant sodas in movie theaters). On the other hand, the individualism of American liberty sometimes morphs in the direction of cold indifference to the struggles of our fellow citizens. Mr. Jefferson spoke nobly against the injustice of slavery as a violation of our rights as free men and women. But he wasn’t ever moved to do much about it. And today members of our “cognitive elite” are amazingly out of touch with those not of their kind, living in a complacent bubble. Puritans, you might say, care too much about what other people are doing, and they say “there ought to be a law” way too to often. But they’re free from the corresponding excess in the other direction: the cruelty of indifference.

Clearly, there is a sense in which men and women are not equals sociologically

29 AugExcerpt from Glen Stanton at First Things:

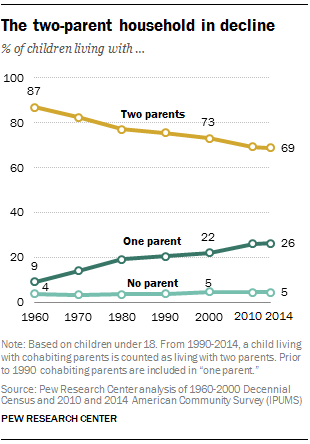

Anthropologists have long recognized that the most fundamental social problem every community must solve is the unattached male. If his sexual, physical, and emotional energies are not governed and directed in a pro-social, domesticated manner, he will become the village’s most malignant cancer. Wives and children, in that order, are the only successful remedy ever found. Military service is a very distant second. Nobel Prize winning economist George Akerlof explains that “men settle down when they get married; if they fail to marry, they fail to settle down,” because “with marriage, men take on new identities that change their behavior.” This does not seem to work with same-sex male couples in long-term relationships.

Husbands and fathers become better, safer, more responsible and productive citizens, unrivaled by their peers in any other relational status. Husbands become better mates, treating their wives better by every important measure—physical and emotional safety, financial and material provision, personal respect, fidelity, general self-sacrifice, etc.—compared to boyfriends, whether dating or cohabiting. Husbands and fathers enjoy significantly lower health, life, and auto insurance premiums than do their single peers, for a strictly pragmatic reason. Insurance companies are not sentimental about husbands. Husbands get lower premiums because they are different creatures in terms of habits, values, behavior, and general health.

This is why Golding’s Lord of the Flies is a tale not so much about the dark nature of humanity as about the isolation of the masculine from the feminine. Had there been just a few confident girls amongst those boys, its conclusion might have been more Swiss Family Robinson

To Christianity from China: conform or else. To Christianity from American government: conform or else?

3 AugBroadly speaking, in China there are two versions of Christianity. There is the one that is officially tolerated, accepted, celebrated, subordinated to, and accommodated by the State in public life. Then there is the one that is officially not tolerated, prohibited, discriminated against, and shunned by the State. Why the unequal treatment? In the former version, the State has determined that it poses no threat to national ideological and cultural orthodoxy and State power. It’s a version of Christianity that will comply with the reigning political elites and their ideological creed, even affirm them. As such, it is rewarded for good behavior with public accommodation. But the latter version, the underground version, has done what all authentic Christian communities have always done on their better days: bend the knee only to the Kingship of Jesus Christ and His Word. They fear God rather than men. It isn’t surprising that such a dichotomy in the 21st century, where a religion is accommodated only in so far as it conforms to a State sponsored creed, exists in communist China, where religious liberty and separation of church/state have never been a fundamental right/principle of the political system. We expect the State to maintain a “conform or else” attitude towards religious communities there. But in America?

Evidence? Where to begin. How about California Senate Bill 1146:

http://www.albertmohler.com/2016/08/03/briefing-08-03-16/

Evangelicals, the Kingdom of God, and Donald Trump

7 JunPerhaps the #NeverTrump debate among evangelicals may in fact boil down to this: should evangelicals be more worried about the nation or the church, the kingdom of heaven or the kingdom of this world? Let’s be clear, voting for Trump, however purely strategic it happens to be, will result in a pro-Trump label for evangelicals (that’s how it will be uncharitably spun). So, how detrimental, shameful, consequential, to the church or kingdom of Jesus Christ will that be? If they reason it won’t be all that detrimental for the cause of Christ and reputation of his church, then a strategic choice to defeat Hillary may be prudent though painful. But if they think that it will be highly detrimental, then they will reason that a Hillary defeat gains little compared to the “mark of Trump” the church will have to bear in the aftermath of the election. Whatever an evangelical does, it seems to me that too few of them are worried about the heavenly kingdom’s reputation and goals and are singularly focused instead on the kingdom of this world.

Do Christian colleges have a right to be Christian colleges?

5 MayFrom Adam Macleod:

Gordon College is still under attack for being an intentionally Christian college. For nearly two years, cultural elites in Massachusetts, led by The Boston Globe, have been waging a sustained campaign of accusation and coercion in an effort to force the college to abandon the self-consciously Christian identity expressed in its life and conduct statement.

The attack appeared existential at one time, when the New England Association of Schools and Colleges announced that it would review Gordon’s accreditation. Yet to its lasting credit, the college has remained steadfast in its witness. After a well-organized and vocal objection by the college’s supportersand other friends of conscience, the NEASC quietly backed down.

Still the attacks continue. Most recently, a former Gordon philosophy professor, Lauren Barthold, has filed suit against Gordon alleging unlawful discrimination. Her complaint is signed by lawyers of the American Civil Liberties Union. The college denies her allegations, explaining that she was disciplined by her colleagues on the faculty not on a legally prohibited basis but because she wrote in a newspaper calling for outsiders to impose economic sanctions on the college. She encouraged others to pressure the college to abandon its Christian moral ideals.

The ACLU’s complaint does not contradict that account. And if recent history is any indication, the full facts will vindicate Gordon College once they surface. None of the accusations leveled against Gordon over the last two years has turned out to be true, except the charge that members of the Gordon College community choose to live biblically. Gordon has not discriminated on the basis of sexual orientation. Indeed, Professor Barthold acknowledges the “many . . . LGBTQ-identified students who have found deep friendships, intellectual growth and spiritual support [at Gordon].”

So, this case is not about Gordon discriminating. This case is about Gordon’s right to be excellent in ways that other Massachusetts colleges and universities are not. The issue is whether Massachusetts courts will preserve the liberty of Gordon’s faculty, staff, and students to maintain an educational community that is unique in its moral commitments. On this point Gordon College can claim an unlikely ally. If the judges of Massachusetts read the writings of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, then they will learn that Gordon College has the right to be differently excellent.

The Constitutional Right to Exclude

In its 2010 decision in the case Christian Legal Society v. Martinez, the Supreme Court of the United States declared and upheld the right of a state university to discriminate against unwanted student groups by excluding them from campus life. The unwanted student groups in Martinez were (who else?) religious groups that require members to live according to moral truths.

What does the Christian church really face after Obergefell?

22 AprFrom Jake Meador:

Hope, History, and the American Church After Obergefell

It’s a truth universally recognized by anyone who has ever talked about the BenOp that a person who expresses concern about the church’s future is in want of a person to quote Tertullian at them.

Sorry, is that cheeky? Here’s the quote and we’ll get to why it grates on my hear so in a moment: “The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church.”

The problem isn’t that Tertullian is always wrong. The problem is that this quote has become a sort of truism reflexively recited by American evangelicals who can only imagine that government-sanctioned opposition to the church will be a good thing for the American church. And while there will likely be some benefits to come from opposition, it’s essential that evangelicals not be overly sanguine about the American church’s short-term prospects.

The Historical Precedent for the Death of Regional Churches

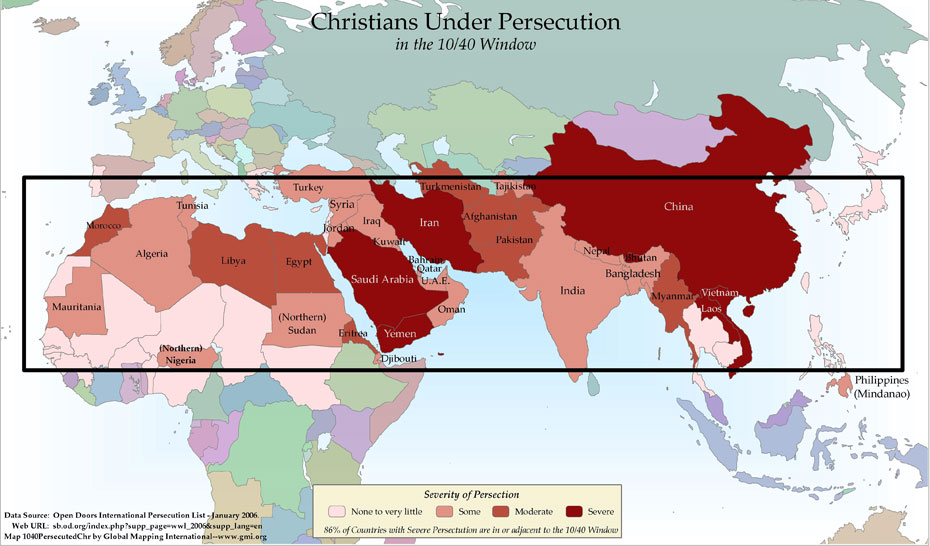

The first point we need to get clear is that, historically speaking, it is simply not true that persecution always helps to strengthen and refine the church. Sometimes persecution simply destroys a church. Once upon a time there were thriving churches in northern Africa, the Middle East, China, and Japan. Then they died. (You can read about them in this fine book by Philip Jenkins.)

Those churches were all either destroyed (in the latter cases) or driven to the very edge of society (in the case of the two former groups). Indeed, what little remained of the historic churches of the Middle East has been largely eradicated by ISIS.

Thus we need to first figure out why these churches were destroyed or simply made into permanent extreme minorities. There are a number of factors in play:

In some cases, the church was closely tied to a ruling elite and when that elite was overthrown the church lost its standing and was crushed.

In other cases, the faith was actually only professed by a small minority of social elites and never penetrated into the mass population.

Finally, in still other cases, Christian identity has become conflated with a set of other characteristics or cultural values which, over time, erode the distinctly Christian characteristics of a people. So there is still a superficial Christianity, but it is badly compromised by its close ties to nationalism. Greece is a good example of this as somewhere between 88 and 98% of the population profess to be Greek Orthodox but only 27% of those people actually attend church weekly. Elsewhere in Europe the numbers are even more dire. In Denmark, 80% of the population is Lutheran but only 3% attend any kind of church service weekly. This critique also applies to cities and states in the USA that are historically Catholic, such as Chicago or Boston. The gap between those who claim to adhere to a specific faith and those who attend church weekly is enormous.

What all this means is that there are a number of conditions that have historically caused local churches to crumble and regional churches to disappear or lapse into a kind of permanent minority status. And the key thing to get clear is that this is very much a live possibility in the United States.

What are the pillars of conservative political thought?

16 MarFrom Alfred Regnery:

Over the past half century, conservatism has become the dominant political philosophy in the United States. Newspaper and television political news stories more often than not will mention the word conservative. Almost every Republican running for office—whether for school board or U.S. senator—will try to establish his place on the political spectrum based on how conservative he is. Even Democrats sometimes distinguish among members of their own party in terms of conservatism.

Although conservatism as we know it today is a relatively new movement—it emerged after World War II and only became a political force in the 1960s—it is based on ideas that are as old as Western civilization itself. The intellectual foundations on which this movement has been built stretch back to antiquity, were further developed during the Middle Ages and in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century England, and were ultimately formulated into a coherent political philosophy at the time of the founding of the United States. In a real sense, conservatism is Western civilization.

The basic foundations of American conservatism can be boiled down to four fundamental concepts. We might call them the four pillars of modern conservatism:

The first pillar of conservatism is liberty, or freedom. Conservatives believe that individuals possess the right to life, liberty, and property, and freedom from the restrictions of arbitrary force. They exercise these rights through the use of their natural free will. That means the ability to follow your own dreams, to do what you want to (so long as you don’t harm others) and reap the rewards (or face the penalties). Above all, it means freedom from oppression by government—and the protection of government against oppression. It means political liberty, the freedom to speak your mind on matters of public policy. It means religious liberty—to worship as you please, or not to worship at all. It also means economic liberty, the freedom to own property and to allocate your own resources in a free market.

Conservatism is based on the idea that the pursuit of virtue is the purpose of our existence and that liberty is an essential component of the pursuit of virtue. Adherence to virtue is also a necessary condition of the pursuit of freedom. In other words, freedom must be pursued for the common good, and when it is abused for the benefit of one group at the expense of others, such abuse must be checked. Still, confronted with a choice of more security or more liberty, conservatives will usually opt for more liberty.

– See more at: https://home.isi.org/node/59819#sthash.TxWUg3gN.dpuf

What has Augustine to do with Neoclassical Economics?

3 FebFrom John Mueller (full article):

I’m grateful to my old friends at the Tocqueville Forum and the Society of Catholic Social Scientists, Patrick Deneen and Steven Brust, and pleased to join John Médaille and Barry Lynn for this discussion of “Economics at the Crossroads.” Though also disconcerted to find myself on this side of the podium. I’ve attended the Tocqueville Forum so often that Tara Jackson said she was surprised I had never submitted an IRS W-9 form. Yet, as Walker Percy warned in Lost in the Cosmos, “a charade was being played” with “William Faulkner, doing a morning’s work, then strolling in the town square to talk to the farmers and have a Coke at Reed’s drugstore…. Though Faulkner went to great lengths to pass himself off as a farmer among farmers, farmer he was not.” Or take “Søren Kierkegaard, who, every hour, would jump up from his desk, rush out into the streets of Copenhagen, and pass the time with shopkeepers. . . ..[B]y his own admission, he was playing the game of being taken for an idler at the very time he was writing ten books a year.” Now I too must admit, every month, by jumping up from my desk, rushing out into the streets of Washington, and passing the time at the Tocqueville Forum, to have been playing the game of being taken for an idler, at the very time I was churning out a book every ten years!

The thesis of my book is straightforward: The most important element in economics is missing, and its rediscovery is priming a revolution the likes of which has occurred just three times in more than 750 years.

I must begin with a simple but widely overlooked fact: the logical and mathematical structures of scholastic, classical and neoclassical economics differ fundamentally. Yet few economists today are aware of the differences because American university economics departments, led by the University of Chicago in 1972, abolished the previous requirement that students of economics master its history before being granted a degree. This calls for a brief, structural history of economics.

What is economics about? Jesus once noted — I interpret this as an astute empirical observation, not divine revelation — since the days of Noah and Lot, people have been doing, and until the end of the world presumably will be doing, four kinds of things. He gave these examples: “planting and building,” “buying and selling,” ‘marrying and being given in marriage,” and “eating and drinking” (Luke 18:27-28). In other words, we produce, exchange, give, and use (or consume) our human and nonhuman goods.

That’s the usual order in our action. But as St. Augustine first explained, the order is different in our planning. First we choose For Whom we intend to provide; next What to provide as means for those persons. Finally, Thomas Aquinas latter added, we choose How to provide the chosen means, through production (always) and exchange (almost always), both of which Aristotle had described.

So, economics is essentially a theory of providence: it describes how we provide for ourselves and the other persons we love, using scarce means that have alternate uses. Human providence is a synonym for the cardinal virtue of prudence. Aristotle had divided moral philosophy into ethics and politics. But he also aptly described humans as “rational,” “matrimonial,” and “political animals.” So Aquinas redivided moral philosophy into three, distinguishing personal, domestic, and political prudence — or equivalently, “economy” — according to the social unit described.

Scholastic ‘AAA’ economics (c.1250-1776) began when Aquinas first integrated these four elements (production, exchange, distribution, and consumption) into an outline of personal, domestic, and political economy, both positive and normative, organizing Aristotle’s contributions according to Augustine’s framework. The scholastic economic theory was taught at the highest university level for more than five centuries by every major Catholic and (after the Reformation) Protestant economic thinker before Adam Smith — notably Lutheran Samuel Pufendorf, whose work was used by Adam Smith’s own teacher to teach Smith economics, and also highly recommended by Alexander Hamilton.

Classical economics (1776-1871) began when Adam Smith cut these four elements to two, trying to explain what he called “division of labor” (specialized production) by production and exchange alone. Smith was addressing the main drawback of scholastic economics, which lay not in the theory itself, but the routine assumption that the economy did not grow in the long run — which had been true on average for about two millennia. To explain growth, Smith and classical followers like David Ricardo undoubtedly advanced the two elements Smith retained. But it was on oversimplification.

Neoclassical economics (1871-c.2000) began when three economists dissatisfied with the practical failure of Smith’s classical outline independently but almost simultaneously reinvented Augustine’s theory of utility, starting its reintegration with the theories of production and exchange.

Thus Adam Smith’s chief significance is not what he added to, but rathersubtracted from economics. As Joseph Schumpeter noted in his History of Economic Analysis, “The fact is that the Wealth of Nations does not contain a single analytic idea, principle or method that was entirely new in 1776.”

Neoscholastic economics (c.2000-). I argue that Neoscholastic economics is already and will continue to revolutionize economics in coming decades, by replacing its lost cornerstone, the theory of distribution.

This historical analysis offers a framework for analyzing other schools of economics. But I will not pursue these lesser differences unless someone asks.

Since Smith essentially “de-Augustinized” economic theory, a re-evaluation is overdue and quite likely for Adam Smith but especially Augustine. So I’ll consider Augustine’s contribution to both scholastic and today’s neoclassical economics, then give an example of the problems in today’s neoclassical economics caused by the failure to restore them, and close with a word about the world views implicit in each theory.

A. Positive scholastic theory. To explain the Two Great Commandments, Augustine had started from Aristotle’s insight that “every agent acts for an end” and his definition of love — willing some good to some person. But Augustine drew an implication that Aristotle had not: every personalways acts for the sake of some person(s). For example, when I say, “I love vanilla ice cream,” I really mean that I love myself and use (consume) vanilla ice cream to express that love (in preference, say, to strawberry ice cream or Brussels sprouts, which reflects my separate scale of utility). Augustine also introduced the important distinction between “private” goods like bread, which inherently only one person at a time can consume, and “public” goods (like a theater performance, national defense, or enforcement of justice) which, at least within certain limits, many people can simultaneously enjoy, because they are not “diminished by being

shared.”

In other words, Augustine’s crucial insight is that we humans always act on two scales of preference — one for persons as ends and the other for other things as means: personal love and utility, respectively. Moreover, we express our preferences for persons with two kinds of external acts. Since man is a social creature, Augustine noted, “human society is knit together by transactions of giving and receiving.” But these outwardly similar transactions may be of two essentially different kinds, he added: “sale or gift.” Generally speaking, we give our wealth without compensation to people we particularly love, and sell it to people we don’t, in order to provide for those we do love. Since it’s always possible to avoid depriving others of their own goods, this is the bare minimum of love expressed as benevolence or goodwill and the measure of what Aristotle called justice in exchange. But our positive self-love is expressed by the utility of the goods we provide ourselves, and our positive love of others with beneficence: gifts. Hate or malevolence is expressed by the opposite of a gift: maleficence or crime.

The social analog to personal gifts is what Aristotle called distributive justice, which amounts to a collective gift: it’s the formula social communities like a family or nation under a single government necessarily use to distribute their common (jointly owned) goods. Both a personal gift and distributive justice are a kind of “transfer payment”; both are determined by the geometric proportion that matches distributive shares with the relative significance of persons sharing in the distribution; and both are practically limited by the fact of scarcity.

That’s “positive” scholastic economics in a nutshell: describing what is, not necessarily what ought to be.

B. Normative” scholastic theory. We naturally love ourselves, Augustine pointed out. All other moral rules are derived from the Two Great Commandments because these measure the degree to which our love is “ordinate”: rightly ordered. If a good were sufficiently abundant we could and should share it equally with everyone else. But with such goods as time and money, which are “diminished by being shared” (i.e., scarce), this is impossible. Therefore “loving your neighbor as yourself” can’t always mean equally with yourself: “All men are to be loved equally. But since you cannot do good to all,” Augustine concluded, “you are to pay special regard to those who, by the accidents of time, place, or circumstances, are brought into closer connection with you.”

The (neo-) scholastic model is a powerful tool of analysis. In the book I suggest several important applications, which I’m willing to discuss at the drop of a question. In view of our severe time limits, though, I will focus here on one simple and striking example: the inverse tradeoff between fatherhood and crime.

In a famous paper co-authored with John J. Donohue and later featured in his book (and now movie) Freakonomics, Steven D. Levitt argued that after abortion was legalized by several states starting in the late 1960s and nationwide by Roe v. Wade in 1973, millions of fetuses were killed who, when old enough, would have been disproportionately likely to commit crimes. Abortion’s culling of them should therefore have lowered crime rates. To prove this, Levitt and Donohue looked at crime rates 15-18 years after Roe and claimed to have found the drop they had predicted.

However, Levitt and Donohue actually found their results indistinguishable whether they used 1970s or 1990s abortion rates to try to explain overall ’90s crime rates. When both were included the models went statistically haywire (“standard errors explode due to multicollinearity”). Failing to uncover any statistically valid evidence for either a 20-year lag or for no lag, Levitt and Donohue replaced the missing facts with an arbitrary assumption: “Consequently, it must be recognized that our interpretation of the results relies on the assumption that there will be a fifteen-to-twenty year lag before abortion materially affects crime.”

They justified their assumption by quipping that “infants commit little crime.” But nearly all violent crime is committed by men (women are equal only in nonviolent crime) precisely the ages of the fathers of aborted children. In short, the missing variable is “economic fatherhood.” (“Economic” fatherhood is defined not by biological paternity nor residency with but provision for one’s children.) The relationship between economic fatherhood and crime is a straightforward application of Augustine’s personal “distribution function” to the most valuable scarce resource of mortal humans: our time.

Including “economic fatherhood” as a variable not only invalidates Levitt’s claim but reverses it. As far back as data exist, rates of economic fatherhood and homicide have been strongly, inversely “cointegrated” — a stringent statistical test characterizing inherently related events, like the number of cars entering and leaving the Lincoln Tunnel. Donohue and Levitt’s correlation is thus shown to be a “spurious regression,” which was misspecified by omitting a crucial variable: the one describing Augustine’s personal “distribution function.” Legalizing abortion didn’t lower homicide rates 15-20 years later by eliminating infants who might, if they survived, have become murderers: it raised the homicide rate almost at once by turning their fathers back into men without dependent children-a small but steady share of whom do murder. The homicide rate rose sharply in the 1960s and ’70s when expanding welfare and legal abortion sharply reduced economic fatherhood, and it dropped sharply in the ’90s partly due to a recovering birth rate, but mostly because welfare reform and incarceration raised the share of men outside prison who were supporting children. [This scenario didn’t occur to Levitt not because of a lack of ingenuity or data but because of the inherent weakness of the theory he was trying to apply, which Nobel Prize-winning economists George J. Stigler and Gary S. Becker, Levitt’s mentor, called the “economic approach to human behavior.” Levitt was unable to see the true correlation between abortion and crime because he was among the first victims of the epic change in the teaching of economics orchestrated by Stigler with Becker’s support].

The choice of 1776. What I call “Smythology” (with two y’s) is the myth that Adam Smith invented or is somehow indispensable to understanding economics. By far the most influential piece of “Smythology” was Milton Friedman’s linking in Free to Choose of “two sets of ideas — both, by a curious coincidence published in the same year, 1776…. the economic principles of Adam Smith…and the political principles expressed by Thomas Jefferson.”Like many others, I found Friedman’s argument persuasive and incorporated it into my own views, until I discovered that the “choice of 1776” was actually a divergence, not a convergence, and of three, not two world views. The third event of 1776 was the death of Smith’s dear friend, the Epicurean skeptic David Hume.

When the Apostle Paul preached in the marketplace of Athens (probably in 51 A.D.), he prefaced the Gospel with a Biblically orthodox adaptation of Greco-Roman natural law. The evangelist Luke tells us that “some Epicurean and Stoic philosophers argued with him” (Acts 17:18). The same dispute has continued ever since, particularly among scholastic, classical, neoclassical, and now neoscholastic e

conomists.

In (neo-) scholastic natural law, economics is a theory of rational providence, describing how we choose both persons as “ends” (expressed by our personal and collective gifts) and the scarce means used (consumed) by or for those persons, which we make real through production and exchange. By dropping both distribution and consumption, Smith expressed the Stoic pantheism that viewed the universe “to be itself a Divinity, an Animal” (as he put it in an early but posthumously published essay), with God conceived as its immanent soul, so that sentimental humans choose neither ends nor means rationally; instead, “every individual…intends only his own gain…and is led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.” By restoring consumption but not distribution, neoclassical economics expresses the Epicurean materialism that claims humans somehow evolved in an uncreated world as merely clever animals — highly adept at calculating means but not ends, since “reason is, and ought only to be, the slave of the passions,” as Hume put it. The three theories provide three views of both human and divine nature, but only the anthropology and theology of the scholastic theory are compatible with Christian orthodoxy.

As historian of economics Henry William Spiegel noted of the “marginal revolution” that ended classical and launched neoclassical economics in the 1870s, “Outsiders ranked prominently among the pioneers of marginal analysis because its discovery required a perspective that the experts did not necessarily possess.” I don’t underestimate the time or effort it will take. But I confidently predict that in coming decades, neoclassical economists now advocating the “economic approach to human behavior” will either become or else be supplanted by “neoscholastic” economists — who will find full employment rewriting neoclassical theory because they understand the original “human approach to economic behavior” of Aristotle, Augustine, and Aquinas.

John Mueller is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C.

Reviewing trajectory of current case law regarding religious vs ‘erotic’ liberty

7 JanVery helpful episode of the “The Briefing” (Al Mohler) today on the current legal landscape (cases and rulings) regarding the ‘collision’ between religious liberty and ‘erotic’ liberty (his word). Basically, current cases indicate a significant narrowing of the ‘religious exemption’ and ‘ministerial exception” language. As you move away from the pulpit, religious organizations are losing their 1st amendment cover and ability to receive these waivers, exemptions, and exceptions to anti-discrimination laws and/or judicial decisions.

World Religions scholar Dr. Timothy Tennet discusses peace within Islam

15 DecHelpful. He breaks it down exegetically, historically, and how modern Muslim scholars re-interpret jihad passages.

Link to the audio: From Biblical Training Lecture Series on Islam

Just another day as a Christian in the 10/40 window

10 Dec

From the Barnabas Fund:

Fire gutted a Christian TV station in Karachi, Pakistan on 24 November, leaving the three-room offices a smouldering wreck following a suspected arson attack.

The blaze, which officials report took nearly two hours to extinguish, appeared to specifically target valuable broadcasting instruments that the station uses to spread the Gospel message to the nation.

Javed William, the brother of Pastor Sarfraz William who is the owner of the affected broadcasting station Gawahi TV, said that the fire seemed to be a deliberate attack aimed at thwarting the Christian work of the station, “This is not an attack on us; it is an attack on Christianity. Whoever did this does not want God’s work to happen.”

Whilst no one was hurt in the incident, the station’s equipment, including computers and cameras, was completely destroyed along with furniture and books. There was also evidence that the network’s security cameras had been tampered with prior to the incident, and some computer hard disks were stolen. Assistant manager of Gawahi TV, Irfan Daniel remarked, “Someone did this with a lot of thought.”

Gawahi Television was established in February 2013 through donations from the Christian community. The station broadcasts Bible readings, Christian hymns and videos with the intention of, “spread[ing] the Gospel of Jesus Christ to people of all religions who live in Pakistan”. The channel, which regularly airs to approximately 12 million people, was working on programming for the Christmas period at the time of the attack.

Previous threats from suspected militants, demanding the closure of the station, were reported to the police by Gawahi TV management, but they did not investigate the threats or give any advice or help to increase security.

A charred but intact Bible was found amongst the wreckage, a fitting reminder of the permanence of the Gospel, even in the face of such raids.

Christian persecution in Pakistan occurs frequently, whether it be through community oppression from the Muslim-majority, discrimination against Christians in the workplace or the unfair implementation of the country’s notorious “blasphemy laws”.

A recent report by the International Commission of Jurists has called on the Pakistan government to, “repeal all blasphemy laws … or amend them substantially so that they are consistent with international standards on freedom of expression; freedom of thought, conscience or religion; and equal protection of the law”.

Is Europe in decline by taking up roots?

8 DecFrom Samuel Gregg:

In his Mémoires d’Espoir, the leader of Free France during World War II and the founder of the Fifth Republic, General Charles de Gaulle, wrote at length about a subject on many people’s minds today—Europe. Though often portrayed as passionately French to the point of incorrigibility, de Gaulle was, in his own way, quintessentially European.

For de Gaulle, however, Europe wasn’t primarily about supranational institutions like the European Commission or the European Central Bank, let alone what some European politicians vaguely call “democratic values.” To de Gaulle’s mind, Europe was essentially a spiritual and cultural heritage, one worthy of emulation by others. Europe’s nations, de Gaulle wrote, had “the same Christian origins and the same way of life, linked to one another since time immemorial by countless ties of thought, art, science, politics and trade.”

On this basis, de Gaulle considered it “natural” that these nations “should come together to form a whole, with its own character and organization in relation to the rest of the world.” However, de Gaulle also believed that without clear acknowledgment and a deep appreciation of these common civilizational foundations, any pan-European integration would run aground.

Today’s European crisis reflects the enduring relevance of de Gaulle’s insight. This is true not only regarding the quasi-religious faith that some Europeans place in the type of supranational bureaucracies that drew de Gaulle’s ire. It also applies to the inadequacies of the vision that informs their trust in such institutions. Until Europe’s leaders recognize this problem, it is difficult to see how the continent can avoid further decline, whether as a player on the global stage or as societies that offer something distinctly enriching to the rest of the world.

On being Intellectually Honest in the Political Islam discussion

23 NovShadi Hamid, Muslim and scholar of Political Islam at Brookings, writes a good piece on the discussion surrounding Islam, democracy, and groups like ISIS. In a day where even asking the question about whether Islam is compatible at its core with democracy and whether ISIS can be quickly dismissed simply as a departure from Islam, his article is poignant.

I’m not a scholar of Political Islam, but in my own area (Christianity and Political Theory), I know it to be intellectually dishonest for me to say that liberal democracy arose in the West despite orthodox Christianity and in no way because of it. From what I know of political Islam and what we observe in history, it is not implausible to say that liberal democracy will arise in the Middle East despite orthodox Islam and not because of it. That is an intellectually honest statement on my part, but it invites charges of bigotry. I will have to live with that.

The reason why the charge of bigotry is sure to follow a statement like that is because of the postmodern liberal fallacy that all religions are the same. They are all equally compatible with liberal democracy or they are all irrelevant to it. Religions are infinitely malleable and can be molded into whatever shape we want. In other words, religions are like cars. They are basically the same, take you to the same places (in this life or the next), and only differ really in furnishings and brand names. But when we buy into this fallacy, we analyze religion and politics using only half our brains.

No, it can be the case, and it isn’t bigotry saying so, that some religions are more or less compatible with liberal democracy than others. It can be the case, and it isn’t bigotry saying so, that some religions require little adjustment for the teachings of their core central figures, sacred texts, to accommodate liberal democracy than others. It can be the case, and it isn’t bigotry to say so, that some religions will need to recover its orthodoxy in order to embrace liberal democracy (I think this is what the Reformation did in church history) while others will need to depart from that orthodoxy and invent something radically new in order to do so.

Hamdi writes: